[Edited by Antonello Mori]

At the beginning of 1641 the Catholic minority in the English kingdom saw a crescendo of violence and discrimination not experienced since the time of Elizabeth I Tudor[1]. Past tensions and present problems were converging in a moment of severe political conflict in the kingdom; the already precarious relationship between Parliament and the Crown was coming to an open fracture, and into this chasm came the pressure of the Puritan components of the Lower House[2].

Amerigo Salvetti accurately reports on this escalation in his avvisi for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. Salvetti, himself a Catholic, points out with intelligence and deep sorrow the whole progression of violence that saw the Parliament and the people of London against the papist minority. The starting point for this documentation will be the avviso of ten May 1641, in which Salvetti writes that the Parliamentarians:

«[…] demanded that the king expel all Catholics from court, disarm those in the kingdom, and dismiss the Irish army. The King took time to answer them, but the parliamentarians returned, so on Wednesday the king said that he was resolved to banish all Catholics from court and would do so as soon as possible without scandal. He would disarm all the Catholics in the kingdom, in accordance with the law, and that there were difficulties in discharging the Irish army, so he would ask their advice»

«[…]Domandano già al re, che volesse cacciare via dalla Corte tutti i Cattolici, disarmare quelli che si trovano nel Regno, et in ultimo di comandare lo sbandamento dell’armata irlandese che si trovava in piedi in quell’Regno. Sua Maestà prese tempo per risponderli, ma vedendo i Parlamentarij che non lo faceva ritornarono a replicarglielo, e così la Maestà sua facendoli venire mercoledì passato alla sua presenza gli disse, che era risoluta di fare uscire dalla Corte tutti i Cattolici, et che l’havrebbe fatto presto, con quelle circumstanze, che si conveni, et senza scandalo. Che voleva che tutti i Cattolici del Regno fussero disarmati, conforme alle Leggi del Regno et che per il disbandamento della Armata irlandese era cosa più da desiderarsi che da eseguirsi per le difficultà che vi incontravano, le quali conveniva prima di superare, desiderando perciò il lor consiglio et assistenza»[3].

Parliamentary pressure, presumably related to a matter of politics rather than faith, also affects the people. The zeal of their reprisals does not even spare the ambassadors of Catholic states such as Spain, as we read here:

«[…] he receives daily insults from this populace, even to the point of threatening to burn down his house, because of his being a good Catholic, and having given shelter in his house to some churchmen»

«[…] riceve ogni giorno qualche affronto da questo popolaccio, fino al minacciarlo di abbraciarli la sua casa, non per altro che per essere buon cattolico, et havere ricoverato nella sua casa alcuni religiosi]»[4].

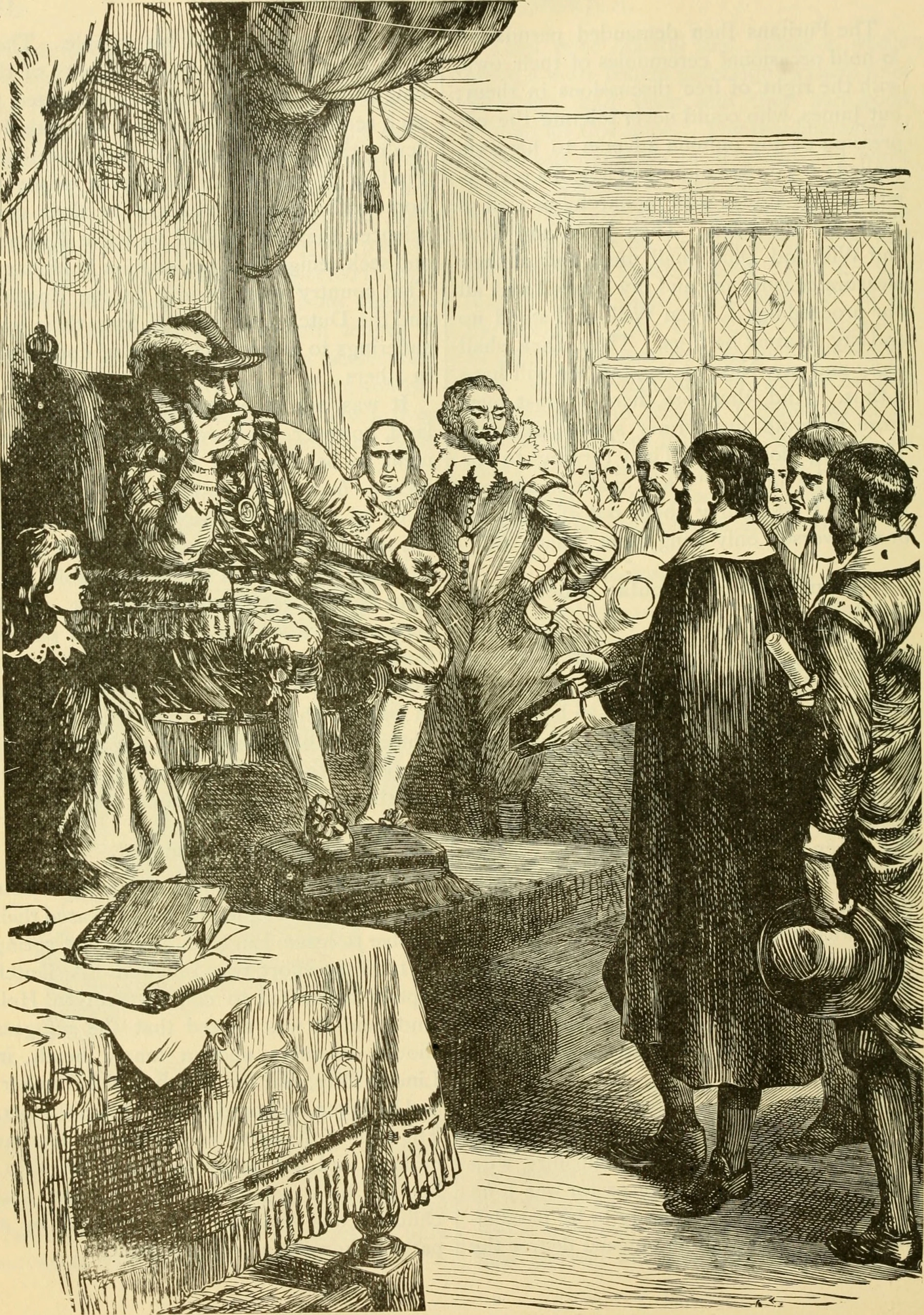

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_puritans_in_conference_with_King_James_I_of_England.jpg

Being Catholic began once again to provoke the kind of prejudice that had characterised England in previous years[5], leading to the reinforcement of group identities also among Anglicans and Puritans, all intent on excluding from “their” land those who did not “belong” there.

Meanwhile the King and Queen appear powerless, deprived of all their prerogatives and at the mercy of a Parliament that denies them any authority. Between the end of July and the beginning of August, religious, social and political tensions in the city of London worsen by the day. On the twelfth of July, Salvetti informs that Count Rossetti, an Italian diplomat living in England, had to take refuge at the Venetian ambassador’s house to avoid being interrogated by Parliament, something that had already happened to the Queen’s confessor[6]. The following week the Venetian ambassador’s confessor was also arrested.

The general frenzy leads the people to carry out summary executions of English and Scottish priests of the Catholic faith, who find themselves being hanged and quartered in the city of London almost on a daily basis:

«Last Monday they hanged and quartered a 70 or 80-year-old English priest, and despite the diligence of the Ambassador of Venice, they also condemned his chaplain to the same fate. The King, however, had his sentence suspended and is working to have him freed. Meanwhile, the Ambassador complains and asks to be compensated for the affront»

«Lunedì passato fecero appiccare et squartare un Sacerdote Inglese, vecchio di 70 o 80 anni, et nonostante la gran diligenza del Signor Ambasciatore di Venezia, condannarono anche nel stesso tempo et al medesimo supplitio il suo cappelano, ma non fu giustiziato, havendo il Re fattone sospendere la giustizia per vedere di libberarlo et renderlo al Ambasciatore, che stride di questo atto fin alle stelle, et ne domanda riparazione»[7].

The city’s Catholic minority thus decided to attempt to appeal to Parliament by petition in the hope of obtaining protection under the law from the generalised violence sweeping through the city. The document was presented on the eighteenth of July, but was ignored[8].

In October 1641, Salvetti informed the Grand Duke that religious and political tensions were becoming more and more palpable, and the situation was worsened by the beginning of the Irish Rebellion, thanks to which the «poor Catholics are watched over, and persecuted with all rigour regardless of who they are. [poveri cattolici sono vigilati, et perseguitati con tutto rigore senza risguardo di persone]»[9].

[1] Roland H. Bainton, La Riforma Protestante, Torino, Einaudi, 2000, pp. 170-193.

[2] Christopher Hill, La formazione della potenza inglese. Dal 1530 a 1780, Torino, Einaudi, 1977, pp.141-143.

[3] MAP, MdP, 4201, documento 52884, f. 12 verso.

[4] MAP, MdP, 4201, documento 52888, f. 19 verso.

[5] James Scott Wheeler, The Irish and British Wars, 1637-1654. Triumph, Tragedy, and Failure, London-New York, Routledge, 2002. pp. 11-36.

[6] MAP, MdP, 4201, documento 52906, f. 68 recto.

[7] MAP, MdP, 4201, documento 52917 e documento 52922, f. 74 verso e f. 81 recto.

[8] MAP, MdP, 4201, documento 52917, f. 75 recto.

[9] MAP, MdP, 4201, documento 52949, f. 135 verso.