[Edited by Miriam Campopiano]

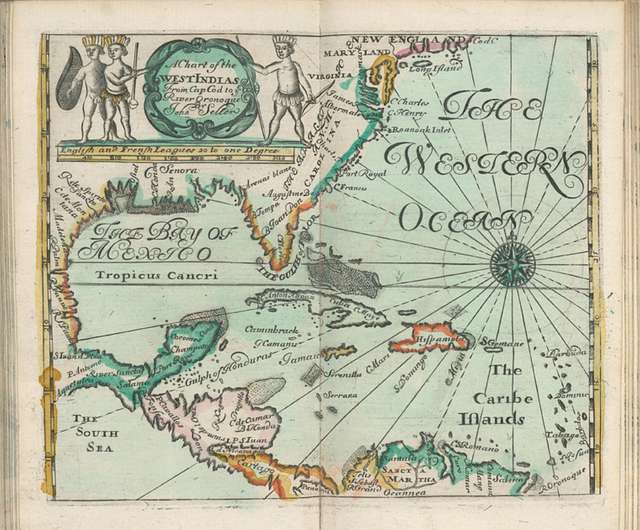

Cromwell’s government was the first one in English history to plan a large-scale invasion in the Americas[1]. Cromwell had a specific plan in mind: to conquer the Spanish territories in the West Indies, and this plan is known as the Western Design. The Western Design was unsuccessful in achieving its goal, in fact it was considered a failure at the time. But it was the first step towards the English expansion in the Caribbean area and the first major stroke to the long-standing enemies, the Habsburgs of Spain[2].

Once in power Cromwell had ended the war with the Dutch, he also hoped that the two nations could cooperate for an alliance between the two governments. He believed that the two protestant republics would benefit from standing together against the power of the Catholic monarchy. The victory over Spain would have also proved God’s favour for the English as the Lord had done since then, supporting the Revolution and the New Model Army. So, in order to bring this vision to life he sent a fleet with very specific orders to take the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean region, expecting an easy victory.

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-1437-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Salvetti reports in his avvisi to Florence the news of this project of conquest (indicating the “island of Santo Domingo”, i.e. Hispaniola, as main goal) and the departure of the fleet on December 1654:

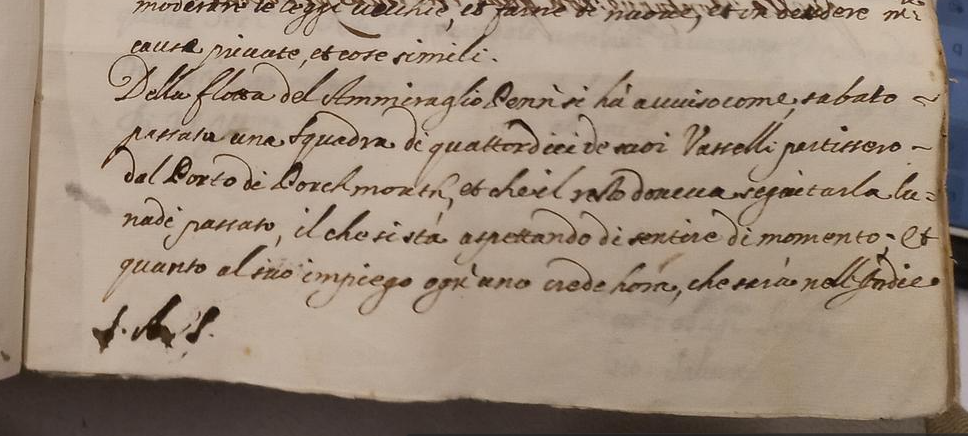

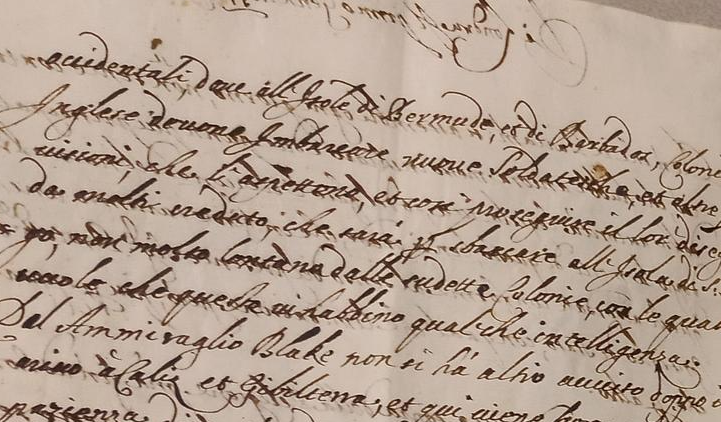

«Della flotta del’ammiraglio Penn si ha avviso come sabato passato una squadra di quattrodici de’ suoi vasselli partissero dal porto di Porchmouth [Portsmouth], et che il resto doveva seguitarla lunedì passato, il che si sta aspettando di sentire di momento, et quanto al suo impiego, ogn’uno crede hora che sarà nell’Indie Occidentali, dove all’isole di Bermude et di Barbados, colonie inglesi, devono imbarcare nuove soldatesche, et altre provisioni che l’aspettono, et così proseguire il lor disegno, da molti creduto che sarà per sbarcare all’isola di S. Domingo, non molto lontana dalle sudette colonie, le quali si vuoli che queste vi habbino qualche intelligenza»[3].

«About Admiral Penn’s fleet it is reported that last Saturday a squadron of fourteen of his vassals departed from the port of Portsmouth, and that the rest were to follow it last Monday, which is waiting to be heard of, and as for its employment, each one now believes that he will be in the West Indies, where the English colonies of Bermuda and Barbados are to embark new troops and other provisions awaiting her, and thus continue their plan, many believe that she will be disembarking on the island of St. Domingo, not far from South America. Domingo, not very far from the aforesaid colonies, which are supposed to have some information there».

Salvetti kept the Medici updated on the expedition, collecting as much news as he could and following the stages of the expedition step by step. To know that sort of information was very important, especially for a family such as the Medici, to be able to make the right political choices. As a matter of fact, news on the New Word and on the extra European world in general appeared in the avvisi only if strictly related to the political or economic spheres. There was, however, a great deal of uncertainty about the expeditions. Cromwell kept secret the real purpose of the expedition even after its departure, that increased the curiosity in the matter, as Salvetti’s avvisi testifies:

«et perché sua altezza non ha fin ad hora publicato quello che portino, qui se ne discorre però molto variamente. […], et sarà cosa dificile di saperne la verità, poiché in corte tutto passa con la solita segretezza».

«and because his Highness has not yet published what they bring, it is discussed here, however, in various ways. […], and it will be difficult to know the truth, since in court everything passes with the usual secrecy».

To conquer the Spanish territory, however, proved to be more difficult than expected. The English were badly organised and unprepared for the Caribbean. Soon after their landing in Hispaniola, the troops were demotivated, dehydrated and ill. The men landed in the wrong location, far away from the city of Santo Domingo, with few supplies in unknown territory. To the English surprise in defence of the island fought also black and mixed race men. The English expected them to be their ally against Spanish rule. After the loss of a thousand men due to diseases and attacks, the English left the island.

Soon enough the first news about the struggling of the English reached London. Unable to return empty-handed, the commanders had to find a new territory to colonise. Thus, landing on the island of Jamaica, where they found less opposition. Here the situation was more in favour of the English expedition but even this success was just partial. The Spanish control on the island was weak but not absent: the island in 1655 was only partially conquered. Furthermore, the action of the English fleet in the Caribbean Sea was the casus belli for the Anglo-Spanish war, a conflict for the control of the routes that would end only in 1660. Ten years later, in 1670 Spain will recognise the English possession of the island with the Treaty of Madrid.

It is understandable why the expedition was considered far from a success at the time. The English conquest of Jamaica, however, was the first step towards the actual expansion of English rule in the Caribbean area and can be seen as a step forward through the English imperial vision.

Further readings

- Gardina Pestana C., English Character and the Fiasco of the Western Design, in “Early American Studies”, Spring 2005, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 1-31.

- Eadem, The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire, Harvard University Press, Cambridge-London 2017.

- Rodger N.A.M., The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815, Norton, New York 2005.

- Taylor S A. G., The Western Design: An Account of Cromwell’s Expedition to the Caribbean, Kingston: Institute of Jamaica and the Jamaica Historical Society, 1965.

- Watson Rannie D., Cromwell’s Major-Generals, in “The English Historical Review”, Jul., 1895, Vol. 10, No. 39 (Jul., 1895), pp. 471- 506.

[1]C. Gardina Pestana, The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire, Harvard University Press, Cambridge-London 2017, p. 1.

[2] Gardina Pestana C., English Character and the Fiasco of the Western Design, in “Early American Studies” , Spring 2005, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring 2005), p. 1.

[3] Archivio di Stato di Firenze, Mediceo del Principato, 4204, f 337v-338r, 7 Agosto 1655.