[Edited by Miriam Campopiano]

Once he reached the peak of power and took control of the English government as Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell focused on planning an English expansion in the Caribbean Sea. The plan, known as Western Design, was to end the Spanish supremacy by conquering their colonies there. The real goal of the expedition, though, was kept secret, so an aura of mystery and curiosity hovered over it. The command of the expedition was entrusted to Admiral William Penn and Robert Venables.

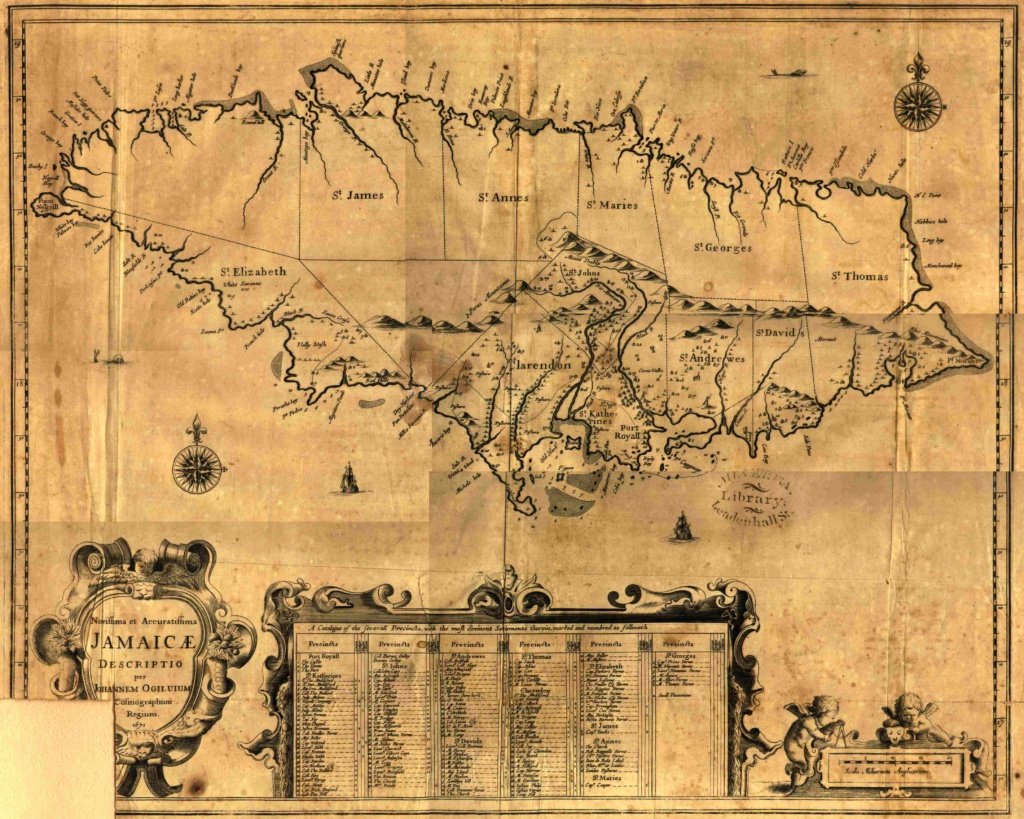

The English fleet set out in December 1654, determined to take the Spanish possession of Hispaniola. But when the English troops arrived on the island, they proved to be unprepared for the climate and the task. The troops soon fell ill with dysentery and were dehydrated, after a few weeks a thousand men had died. At this point the expedition left Hispaniola and it turned to the island of Jamaica, which eventually they succeeded to conquer.

Jamaica1671ogilby.jpg (4329×3461) (wikimedia.org)

There were several reasons for this failure: disorganisation, the environment and tropical diseases that strained the men, but not least bad leadership and personal rivalries. The two commanders, Penn and Venables, had already had a difficult relationship in the past, which became even more complicated after their failure.

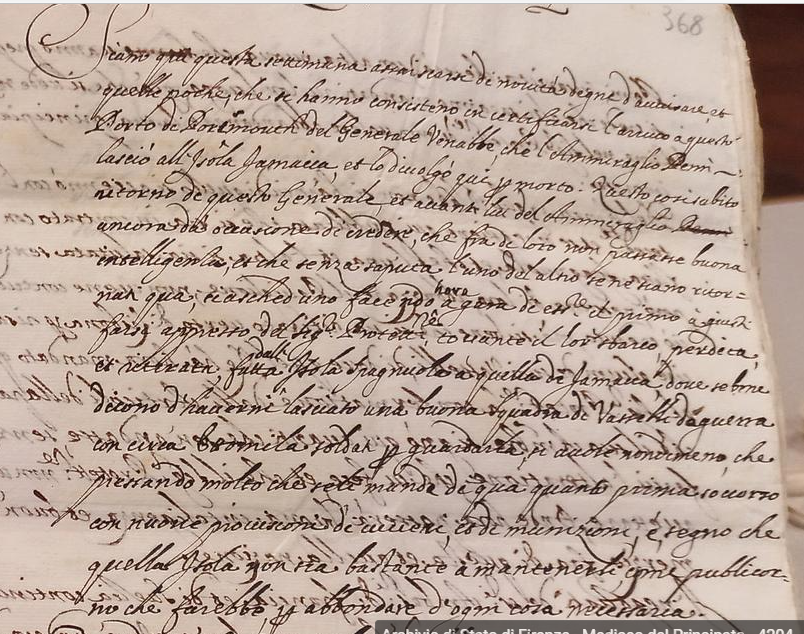

This is testified by the avvisi that Amerigo Salvetti sent to Florence. We even read in an avviso that on his return from the island, Penn announced Venable’s death, even though he was not dead at all. The fake news was disproved by the arrival of Venable himself in London. Both commanders left the conquered island to reach London and hope to have their version of the story prevail over the other.

«Siamo qui questa settimana assai scarsi di novità degne d’avvisare, et quelle poche che si hanno, consistono in certificarsi l’arrivo a questo porto di Portsmouth del generale Venable che l’ammiraglio Penn lasciò all’isola Jamaica, et lo divolgò qui per morto. Questo così subito ritorno di questo generale et avanti lui del’ammiraglio ancora, dà occasione di credere che fra di loro non passasse buona intelligenza, et che senza saputa l’uno del’altro se ne siano ritornati qua, ciascheduno facendo hora a gara d’essere il primo a giustificarsi appresso del signor Protettore, toccante il lor sbarco, perdita et ritirata fatta dall’isola Spagnuola a quella di Jamaica, dove se bene dicono d’havervi lasciato una buona squadra di vasselli da guerra, con circa ottomila soldati per guardarla, si vuole nondimeno che pressando molto che se li mandi di qua, quanto prima soccorso con nuove provisioni di viveri et di munizioni, è segno che quella isola non sia bastante a mantenerli, come publicorno che farebbe, per abbondare d’ogni cosa necessaria».

«We are here this week with very little newsworthy of notice, and the few that we have, consist in certifying the arrival at this port of Portsmouth of General Venable, whom Admiral Penn left in Jamaica, and announced here for dead. This immediate return of this general, and of the admiral before him, gives occasion to believe that there are not good relations between them, and that unbeknownst to each other they have returned here, each one now competing to be the first to report to the Lord Protector about their landing, loss and retreat from the island of Hispaniola to that of Jamaica, where if they say that they have left a good squadron of vassals of war there, with about eight thousand soldiers to guard it, they nevertheless want to press hard for them to be sent from here, as soon as possible, with new provisions of provisions and ammunition, it is a sign that that island is not sufficient to maintain them, as they said it would be, to have plenty of everything necessary».

After they had reported and justified the reasons for the loss, Cromwell’s reaction was very severe: he imprisoned them in the Tower of London for dissertation, because they had left the island without the necessary authorization. Once the real goal of the expedition and its outcome became public knowledge, the reaction was of discontent. Cromwell had invested not only money and man in the Western Design, but also the idea of English superiority. Thanks to its army and God’s favour England would have had the best over its Catholic competitor. So, now that the expedition had been revealed to be a fiasco all these ideas too were contested. The Western Design had let the expectations down and someone needed to take the blame. The two commanders were held responsible, but the one whose reputation suffered the most was Vernon.

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/14419.html

All images must be credited © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Penn was be released relatively quickly, but Venable persisted with his attitude that had been annoying his colleagues and superiors for some time, instating that he was not to blame for the failure[1]. He had already shown this kind of behaviour during the expedition, this was one of the reasons that damaged the relationships with Penn. In any case, he too was eventually released, but this can be said to be the end of his naval career. As for Penn, after being released he retired to Ireland for a few years. In 1660, after the Restoration, he pursued a political career.

Further readings

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Sir William Penn”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 Apr. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Penn-British-admiral. Accessed 29 July 2022.

- Gardina Pestana C., English Character and the Fiasco of the Western Design, in “Early American Studies” , Spring 2005, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring 2005), pp. 1-31.

- Eadem, The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire, Harvard University Press, Cambridge-London 2017.

- Rodger N.A.M., The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649-1815, Norton, New York 2005.

- Taylor S A. G., The Western Design: An Account of Cromwell’s Expedition to the Caribbean, Kingston: Institute of Jamaica and the Jamaica Historical Society, 1965.

- Venables, Robert, 1612?-1687, and C. H. (Charles Harding) Firth. The Narrative of General Venables: With an Appendix of Papers Relating to the Expedition to the West Indies And the Conquest of Jamaica, 1654-1655. London: Longmans, Green, and co., 1900.

- Watson Rannie D., Cromwell’s Major-Generals, in “The English Historical Review”, Jul., 1895, Vol. 10, No. 39 (Jul., 1895), pp. 471- 506.

[1] C. Gardina Pestana, The English Conquest of Jamaica: Oliver Cromwell’s Bid for Empire, Harvard University Press, Cambridge-London 2017, p. 137