[Edited by Enrico De Prisco]

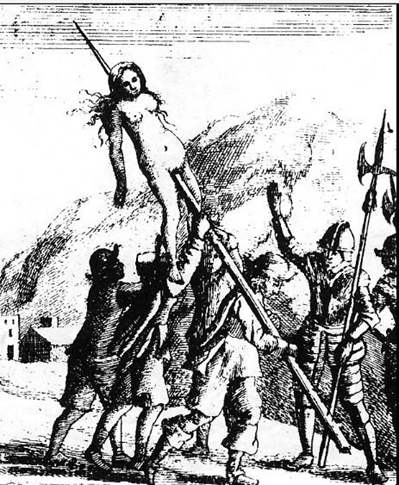

In mid-April of 1655, the Savoyard militias, backed by a regiment of Irish Catholic soldiers serving in the French army, started the military operation against the Waldenses community of Val Pellice, in the mountains surrounding Turin in Piedmont. This tragic epilogue came to fruition after a period of instability and conflict between the Waldenses communities and the Savoyard authorities of Turin. The attempted blitz of April, when the Savoyard army assaulted Torre Pellice, started a period of continuous skirmishes in the valley areas between the ducal troops and the Waldenses’ popular militia. The so-called “Piedmontese Easter”, the massacres perpetrated by the Catholics with Holy week, generated a media case in the Europe of the mid-XVII century.

Waldenses’ strategies consisted of publicizing the horrific stories of the violence inflicted on them by the Savoyard and French troops to give an international echo to their tragedy. As a result of the violent action employed by the Savoyard government, a wave of indignation crossed Protestant Europe whole. Above all, Geneva, England and the Netherlands demonstrated solidarity with their persecuted fellow worshippers.

Indeed, this indignation was recorded mainly in Cromwell’s England. According to Amerigo Salvetti, the Tuscan Resident in London, the news of these massacres coming from Piedmont strongly impacted the English society of the time, who worried for the fate of the Piedmontese Protestants. Salvetti noted how this news excited the English audience’s spirit, stoking the anti-Pope popular sentiment. In the avviso of 18 June 1655, Salvetti wrote:

«Le stampe che questa settimana si vendono et credino [sic gridano?] per questa città, toccante le atroci crudeltà che esse publicano essere state fatte da’ franzesi et Savoiardi ai protestanti sudditi del signor duca di Savoia [Carlo Emanuele II di Savoia], ha messo questo popolo in tanto furore et ira contro de’ cattolici che si può dubitare che non ne faccino qualche risentimento contro di loro».

«The prints that are being sold and proclaimed this week in this city [London], touching upon the horrible cruelty committed by the French and Savoyard against the protestant subject of the Duke of Savoy (Carlo Emanuele II), [the atrocities] have instilled in this people much ire and the fury against the Catholics, so that may [not] be doubted that they do not bear some resentment against them».

An opinion trend arose in England on the emotional wave caused by the events in Piedmont. Even the great poet John Milton, friend and supporter of Oliver Cromwell, wrote a passionate sonnet titled “On the late massacres in Piedmont”, touched by the recounts of the massacres perpetrated by the Catholics.

Salvetti continued the avviso by describing the first reactions of the English government to the Waldenses’ affair. Here we read that:

«The Lord Protector has shown himself sensitive, and he has demonstrated through a broad declaration which he has sent for to be printed, blaming such as a barbarian and shocking cruelty. He has ordered that on the 24 of this month, fasting and prayer be held in this city’s churches. The aim was to comfort their poor protestant brothers, who were fiercely persecuted. He [Cromwell] also ordered the preacher to exhort their audience to contribute liberally with large donations».

At the same time, Cromwell must have seen in this affaire the chance of earning significant advantages for his international prestige and his Country’s interests.

«In addition, Lord Protector sent a letter to the Duke of Savoy with an express courier in the past week. [In the letter, the Lord Protector] protested the aversion for the abuse the Duke of Savoy was doing against his Protestant subjects. [The Lord Protector] moreover requested [to the Duke] to put an end [this situation], to not give him the excuse for doing it».

Indeed, it is clear that Oliver Cromwell seized the occasion to emerge the grand champion of the Protestant cause in Europe, taking the Waldenses and their cause under his protection. Cromwell, moreover, used the clashes happening in Piedmont to achieve better conditions for his Country in the ongoing treaties with Cardinal Mazarin and Louis XIV of France, accusing the French monarchy of complicity in the massacres.

«Si vuole che nella spedizione che nel’istesso tempo fece del’altro espresso al Christianissimo [Louis XIV de Bourbon] fusse per il medesimo effetto, havendo avviso che uno de’ generali che trattorno così male quei protestanti fusse franzese et comandante un reggimento d’irlandesi. [18 giugno]»

«It is heard that the expedition he sent at the same time as the other express [courier] to the King of France was for the same thing because he [Cromwell] had received news that one of the generals who abused the Protestants was French and commander of an Irish regiment. [18 June 1655]»

«[…] Pare che la causa che ha disgustato quelli che governano in Francia, sia stata quella del’havere la lettera del signor Protettore addossato ai franzesi buona parte delle crudeltà che qui si divolgò essere state fatte ai protestanti di Savoia, alla quale la Francia del tutto nega d’haversi hauto parte, et che dette crudeltà non sono punto della qualità che qui le dipingono. Contuttociò, comonque sia, l’affare resta hora alquanto incagliato. [25 giugno]»

«[…] It seems that the cause which disgusted the French government was the letter of the Lord Protector in which he accused the French of participating in the cruelty against the Protestant of Savoy, as it was published here (in London). The French absolutely denied their participation and that these cruelties were not as depicted here. Having said this, the affaire remains as of now quite tangled. [25 june 1655]»

In Salvetti’s reports, we often read references to printed matters circulating in England on the “Piedmontese Easter”, making us clear how the spreading of news could influence international politics in the XVII century. In this case, we note how information changed the balance of power, helping a small community of peasants and farmers of the remote Alpine valleys of Piedmont to surge on the European proscenium, gaining the attention of one of the most powerful nations in Europe.

On the other side, the English government, in the person of Oliver Cromwell, as we have yet said, took advantage of the situation to gain international rule. This operation was conducted especially thanks to the work of two men: Jean-Baptiste Stouppe, a Protestant preacher and a libertine (such a singular personality in the European panorama!), and Samuel Morland, Cromwell’s extraordinary envoy to king Louis XIV of France and to Carlo Emanuele of Savoy and English extraordinary ambassador to Geneva. The two Cromwell’s agents– in particular Stouppe – contributed to translating the Waldenses pamphlets into English, playing a crucial role in propagating the victims’ version of the atrocity in England.

This media operation did not go unnoticed by Salvetti, who did not fail to convey his opinion on the matter to Grand Duke Ferdinando II. In the avviso of 16 July, he wrote:

«Si continua qui sempre più sensitivo della crudeltà che queste stampe vanno del continuo gridando in questa città d’essere state usate contro delli ugonotti di Savoia, le quali, benché incontrino oppositione, et che manifestino l’affare del tutto contrario et in favore del signor duca di Savoia [Carlo Emanuele II di Savoia], non per questo lasciono qui di esagerare et di aggrandire le dette crudeltà, et di addossarle omninamente ai cattolici, […]»

«Printed matters even more emotional are still propagating in this city [London] on the cruelties perpetrated against the Huguenots of Savoy. These prints have not been desisting to exaggerate the acts of violence, charging the Catholics with the responsibility, although [prints] described the affair differently, in a way favourable to the Duke of Savoy […]»

Further readings:

Martino Laurenti, I confini della comunità. Conflitto europeo e guerra religiosa nelle comunità valdesi del Seicento, Turin, Claudiana, 2015

Stefano Villani, “A man of intrigue but no virtue” Jean-Baptiste Stouppe (1623–1692), a Libertine between Raison d’État and Religion, in ‹‹Church history and religious culture››, 2021, n.101, 306-323

Stefano Villani, Translating a massacre. Jean-Baptiste Stouppe and the Waldensian slaughter of 1655 between propaganda, religion and diplomacy, in ‹‹Rivista di letteratura storiografica italiana›› pp. 121-136