[by Brendan Dooley]

Charles I, son of James I (VI of Scotland) and Anne of Denmark was born in Scotland on November 19, 1600. Crowned King of England and Ireland on 2 February 1626, and of Scotland on 18 June 1633, he was executed on 30 January 1649 at Whitehall.

Was he mostly loved or hated?

At least one of his faithful courtiers left a (mostly) flattering tribute.

Sir_Anthony_Van_Dyck_-_Charles_I_(1600-49)_-_Google_Art_Project. Public domain.

But here we give two contrasting opinions by contemporaries of the King, starting with a Venetian ambassador.

Angelo Correr served as Venetian Ambassador in England from 1634 to 1637, after which, as required by his office, he submitted to the Doge and Senate a detailed report on the country, the government, and the people. Although impressed with Charles I’s aptitude and virtues, he saw a another side which in his view could have possible negative repercussions in future. Did he foresee the civil war? Let’s see:

First, the attitude to warfare: “The present king, although born with very different moods from his father, has encountered accidents, no less, which make him follow the same rules. He is peaceful, but out of necessity, there being nuances which show him inclined to war; and he would undertake this if, in order not to submit to the indiscretion of his subjects, he were not forced to abandon the thought of them.” This is said of a man who “wields weapons like a knight, and his steed like a horseman.”

Next, the attitude to others: “He is not prodigal like his father, but neither is he liberal, when the tightness of his treasury is not the cause. He has no vices or luxuries, but he is severe and more serious than familiar. … He is not subject to amorous affairs, nor has he had favorites after the Duke of Buckingham’s death. He chooses ministers, not out of affection, but out of an opinion of adequacy. He is never extreme; except in that he perseveres where he inclines, and whoever is once abhorred by him can be sure never to return to his favor.”

Now the possible downfall: “Of the paternal characteristics, he has inherited two: that is, hunting, and a dislike, not to say antipathy, for the people, which after all is well known to be the last pole of his movements, the only cause that makes him peaceful, and the indicator that will determine whether he does well or badly.”

The dismissal of the Short Parliament shows a dangerous trend: “Having given up governing by parliaments as his predecessors did, now it remains to be seen whether he will continue and whether he will be able to do with royal authority what past kings did with the authority of the whole kingdom.”

Correr considered the whole matter to be “a difficult business, but all the more dangerous since, if it is true that States are disturbed by the two great causes of religion and the extension of freedom among peoples, he has meddled with both; only a stroke of luck will prevent him from succumbing to some great turmoil.”

Prophetic words in 1637!

Now the courtier.

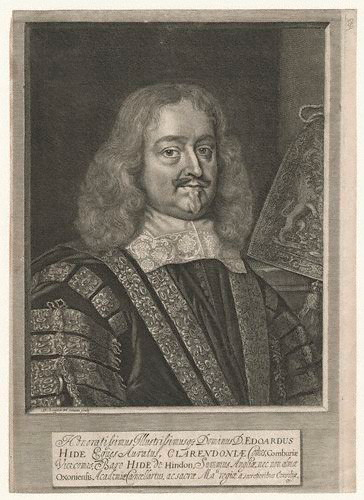

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (d. 1674), served as chief advisor to Charles I during the First English Civil War, and Lord Chancellor to Charles II from 1660 to 1667.

In his autobiography (Life of Edward, Earl of Clarendon, part 1, p. 56) he describes the situation of the Three Kingdoms of England Scotland and Ireland on the brink of the Civil War.

“Of all the princes of Europe, the King of England alone seemed to be seated upon that pleasant promontory, that might safely view the tragic sufferings of all his neighbours about him, without any other concernment, than what arose from his own princely heart and christian compassion, to see such desolation wrought by the pride, and passion, and ambition, of private persons, supported by princes, who knew not what themselves would have. His three kingdoms flourishing in entire peace, and universal plenty; in danger of nothing but their own surfeits; and his dominions every day enlarged, by sending out colonies upon large and fruitful plantations; his strong fleets commanding all seas, and the numerous shipping of the nation bringing the trade of the world into his ports; nor could it with unquestionable security be carried any where else.”

“O fortunati nimium, bona si sua norint! In this blessed conjuncture, when no other prince thought he wanted any thing to compass what he most desired to be possessed of, but the affection and friendship of the King of England: a small, scarce discernible cloud, arose in the north, which was shortly after attended with such a storm, that never gave over raging, till it had shaken, and even rooted up, the greatest and tallest cedars of the three nations; blasted all its beauty and fruitfulness, brought its strength to decay, and its glory to reproach, and almost to desolation; by such a career and deluge of wickedness and rebellion, as by not being enough foreseen, or in truth suspected, could not be prevented.”

The Earl of Clarendon; 1666 engraving by David Loggan. Public domain.

In his History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England: Begun in the Year 1641 by Edward Hyde (d. 1674), 1st Earl of Clarendon (3 volumes) (1702–1704)

Clarendon offers a carefully detailed assessment of Charles as a person.

“To speak first of his private qualifications as a man, before the mention of his princely and royal virtues; he was, if ever any, the most worthy of the title of an honest man; so great a lover of justice, that no temptation could dispose him to a wrongful action, except it was so disguised to him that he believed it to be just. He had a tenderness and compassion of nature, which restrained him from ever doing a hard hearted thing: and therefore he was so apt to grant pardon to malefactors, that the judges of the land represented to him the damage and insecurity to the public, that flowed from such his indulgence. And then he restrained himself from pardoning either murders, or highway robberies, and quickly discerned the fruits of his severity by a wonderful reformation of those enormities. He was very punctual and regular in his devotions; he was never known to enter upon his recreations or sports, though ever so early in the morning, before he had been at public prayers; so that on hunting days his chaplains were bound to a very early attendance. He was likewise very strict in observing the hours of his private cabinet devotion; and was so severe an exactor of gravity and reverence in all mention of religion, that he could never endure any light or profane word, with what sharpness of wit soever it was covered: and though he was well pleased, and delighted with reading verses made upon any occasion, no man durst bring before him any thing that was profane or unclean. That kind of wit had never any countenance then. He was so great an example of conjugal affection, that they who did not imitate him in that particular, durst not brag of their liberty: and he did not only permit, but direct his bishops, to prosecute those scandalous vices, in the ecclesiastical courts, against persons of eminence, and near relation to his service.

“His kingly virtues had some mixture and alloy, that hindered them from shining in full lustre, and from producing those fruits they should have been attended with. He was not in his nature very bountiful, though he gave very much. This appeared more after the Duke of Buckingham’s death, after which those showers fell very rarely; and he paused too long in giving, which made those to whom he gave, less sensible of the benefit. He kept state to the full, which made his court very orderly; no man presuming to be seen in a place where he had no pretence to be. He saw, and observed men long, before he received them about his person; and did not love strangers, nor very confident men. He was a patient hearer of causes; which he frequently accustomed himself to, at the council board; and judged very well, and was dexterous in the mediating part: so that he often put an end to causes by persuasion, which the stubborness of men’s humours made dilatory in courts of justice.

“He was very fearless in his person; but, in his riper years, not very enterprizing. He had an excellent understanding, but was not confident enough of it; which made him oftentimes change his own opinion for a worse, and follow the advice of men that did not judge so well as himself. This made him more irresolute than the conjuncture of his affairs would admit: if he had been of a rougher and more imperious nature, he would have found more respect and duty. And his not applying some severe cures to approaching evils, proceeded from the lenity of his nature, and the tenderness of his conscience, which, in all cases of blood made him choose the softer way, and not hearken to severe counsels, how reasonably soever urged. This only, restrained him from pursuing his advantage in the first Scottish expedition, when, humanly speaking, he might have reduced that nation to the most entire obedience that could have been wished. After all this, a man might reasonably believe that nothing less than an universal defection of three nations could have reduced a great king to so hard a fate; it is most certain, that, in that very hour when he was wickedly murdered in the sight of the sun, he had as great a share in the hearts and affections of his subjects in general, was as much beloved, esteemed, and longed for by the people in general of the three nations as any of his predecessors had ever been.

“To conclude, he was the worthiest gentleman, the best master, the best friend, the best husband, the best father, and the best Christian, that the age in which he lived produced. And if he were not the greatest king, if he were without some parts and qualities which have made some kings great and happy, no other prince was ever unhappy who was possessed of half his virtues and endowments, and so much without any kind of vice.” III. 256.

FURTHER READING

Angelo Correr, “Relazione d’Inghilterra,” in Le Relazioni degli stati europei lette al Senato dagli ambasciatori veneziani nel secolo decimosettimo, raccolte ed annotate da Nicolò Barozzi e Guglielmo Berchet. ser IV Inghilterra, volme unico, Venice: Naratovich, 1863, pp. 317-41.

History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England: Begun in the Year 1641 by Edward Hyde (d. 1674), 1st Earl of Clarendon (3 volumes) (1702–1704)

The Life of Edward, Earl of Clarendon written by himself, vol. 1 London: Clarendon, 1760, part 1, p. 56.