[By Brendan Dooley]

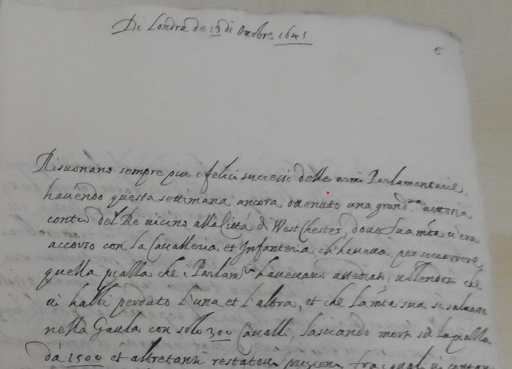

The handwritten newsletter dated from London on 13 October 1645 and read shortly thereafter at the Grand Ducal court in Florence, began thus:

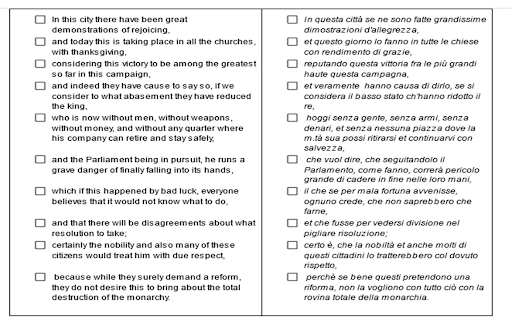

“In this city there have been great demonstrations of rejoicing, and today this is taking place in all the churches, with thanksgiving.”

What was the fuss all about? The Battle of Rowton Heath has just occurred, preventing the Royalist forces from relieving the loyal city of Chester, now under siege by the Parliamentarians.

Things were going very badly for the king. The newsletter continues about how everyone is

“considering this victory to be among the greatest so far in this campaign, and indeed they have cause to say so, if we consider to what abasement they have reduced the king, who is now without men, without weapons, without money, and without any quarter where his company can retire and stay safely, and the Parliament being in pursuit, he runs a grave danger of finally falling into its hands.”

As might be expected, the writing bears the stamp of its origin, and traces of its original environment.

We continue in Salvetti’s words, where he says, if the Parliament prevails,

“everyone believes that it would not know what to do, and that there will be disagreements about what resolution to take; certainly the nobility and also many of these citizens would treat [the king] with due respect, because while they surely demand a reform, they do not desire this to bring about the total destruction of the monarchy.” His conclusion is not exactly flattering in regard to Cromwell, Fairfax and the rest. He says, “The greatest current danger lies in the people now in authority, and their resolution to remain there, not wishing to see the King back in this city in any way.”

It was a view, and an emotional reaction, that his audience in the monarchical state of Florence could be expected to share, and even to esteem.

But let’s look at our newsletter. The example we have been using here illustrates a typical style of newsletter composition, with long run-on sentences or periods (periodi, as the Latin language secretarial schools would call them), shown in the following table:

We may hypothesize about the dynamics of this format, in regard to the attempt to proceed from brain to page with no intermediate notes or other intervening steps, for the sake of speed and saving paper. For all the regularity of composition and even occasional elegance, these are not finished pieces by any means; but they do give a sense of first impressions regarding the issues at hand.

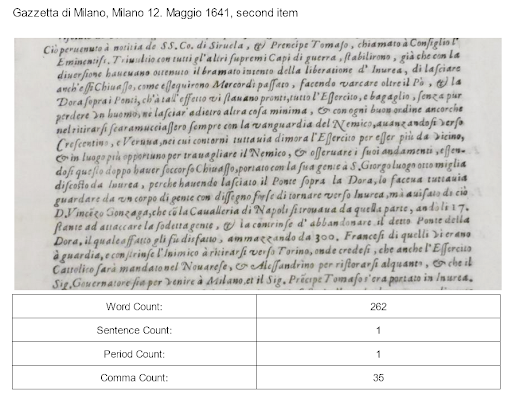

Any doubt that this style might be unique to Salvetti is removed by comparison with the first Italian newspapers, bearing considerable similarities to such diction. Consider for example this copy of a newspaper from Milan dated 12 May 1641, where we find the same kind of run-on clauses resembling a stream of consciousness, here devoted to an account of the most recent French attempts, under Cardinal Richelieu, to seize territory within the Duchy of Savoy against pro-Spanish forces.

The image of the relevant page in the gazette demonstrates the advantages of print at least from the standpoint of cramming material into a smaller space; but the presence of a single 262-word “period” or sentence shows obvious stylistic similarities to Salvetti’s handwritten text. Clearly, the given diction and syntax were perfectly suited to the composition practices of early news, and were regarded as being so.

The breathless flow of words not only contains concepts showing actions having been carried out, but also attitudes belonging to the writer (and perhaps assumed also to exist among possible readers). As time goes on, Salvetti reveals himself to be no friend of the revolutionaries. This is a feature he shares with many in the international community, and in particular with the Venetians, and Stefano Villani has drawn attention to the seemingly paradoxical attitudes of the latter, who appeared to be sympathetic to the king rather than the Parliament, viewing the monarchy as the ideal mix of the three classic forms, of monarchical, aristocratic and democratic, not unlike their own. Salvetti on the other hand wrote fully in coherence with the monarchical position, nonetheless recognizing the weakness of the particular monarch who was Charles I; but more particularly he expressed his dislike for Cromwell and the army.

When things look progressively dismal for the king, Salvetti explains how and why. In a letter accompanying another newsletter, referring to the Parliament, he exclaims,

“In conclusion, they want to have war until they succeed in bringing everything under their control, which they will certainly succeed in doing, as they have the means to do it, and have reduced the poor king to where he cannot regain power except by a miracle.”

The aspect of divine aid was by no means a vain aside; post-Machiavellian doctrines about power present not only in Northern European political culture but also the Italian counterpart, including by the Florentine courtier Scipione Ammirato, made frequent reference to the orderly convenience of a hierarchically arranged structure of society under a representative of the deity. Salvetti seems to agree.