[Edited by Davide Limatola]

«Here this week, some gentlemen have been imprisoned in the Tower of London, without the real cause being known, despite it usually being public, to be found that they had conspired against the person of the Lord Protector»

«Qui sono questa settimana stati fatti mettere prigioni in questa Torre di Londra alcuni gentil’huomini, senza sapersene per ancora la vera causa, benché generalmente venga divolgata, trovarsi che havessero machinato contro la persona del signor Protettore»[1].

With these words, Amerigo Salvetti, Florentine resident to London, notifies the secretariat of Ferdinand II of the tension that can be felt in London in the summer of 1654. Oliver Cromwell had taken the title of Lord Protector around six months prior, but the royalist faction, at the command of Charles II Stuart, was still an influential force in Albion. They were called mainly in Ireland and in Scotland at the orders of Count John Middleton, royalist troops opposed a proud refusal to the authority of the new English Protector. Not only this, the men faithful ot the Stuart cause were also present in France and in the United Provinces, two main English fears beyond the Channel.

(c) National Trust, Castle Ward; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

The new English Republic did not only have external enemies to fear, but several internal enemies bustled around the streets of London: old counts and barons had lost power and influence, religious factions opposed the renewed rigid Anglican orthodoxy, as with the Anabaptists, and gentlemen who were still tied to the monarchic ideal were only among the main dangers for Cromwella and his Council of State.

As reported by Amerigo Salvetti, internal dangers were the main fear of the Lord Protector, who is «very sensitive and troubled, and who along with his Council of State is with extreme diligence trying to see the bottom of this, and to punish the conspirators, as a cause of public unrest and of the present government [vede esserne molto sensitivo et travagliato, et che insieme col suo Consiglio di Stato fa estraordinaria diligenza per toccarne il fondo, et in ordine punire i cospiratori, come perturbatori della publica quiete et presente governo]»[2]. This is why, in the spring-summer of 1654, police activity intensified in London and in the main English cities to uncover possible conspiracies against the Republic.

«[…]because his Highness fears that many others are involved in this plot against him, he commands that every house in London be visited, and that every dweller be recorded, as he has commanded that nobody leave it, during the space of ten days»[3].

«[…]vede esserne molto sensitivo et travagliato, et che insieme col suo Consiglio di Stato fa estraordinaria diligenza per toccarne il fondo, et in ordine punire i cospiratori, come perturbatori della publica quiete et presente governo».

Night incursions were organised for the purpose of spotting possible organised royalist groups:

«[…] his Highness has commanded to several military officials that, along with many soldiers, they go to visit every house that is suspect of hiding suspicious people if they are not able to explain their ilves, and to gather the written names not only of the owners of the house, but also of those who dwell theres»[4].

«[…] perché sua altezza teme che molti altri siano impegnati in questa congiura contro di lui, ha comandato che tutte le case di Londra siano visitate, et preso i nomi di quelli che vi abitano, come anche comandato che nessuno debba sortire fuori d’essa, durante lo spazio di dieci giorni».

The search for men linked to the plot continued throughout the whole summer: the first avviso in which Salvetti mentions the conspiracy is an avviso dated 5 June 1654. In all of the following ones – Salvetti writes to Florence every 7-8 days – the plot is a recurring topic, one a careful observer can’t help noting. Even when news is scarce, Salvetti feels the need to repeat the previous weeks’ statements adding a few new comments each time. Only at the end of August, with the avvisi of the 21st and the 28th, news regarding the plot start fading from the reports: a new topic galvanises attention: the coming opening at the beginning of September of the new Parliament.

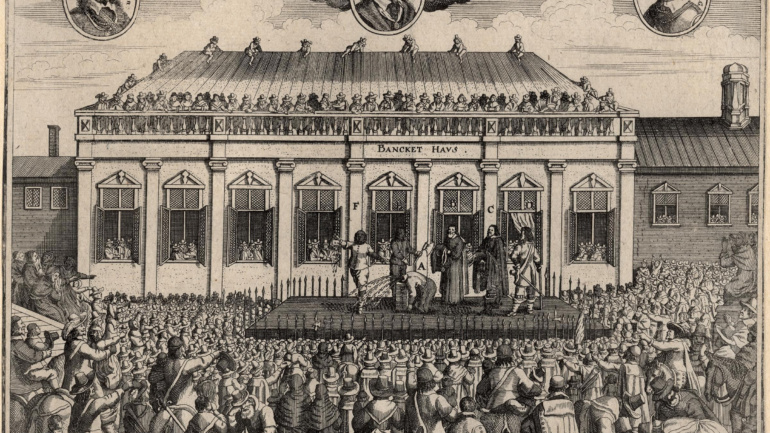

As June was the month of policing, July was the month of trials. Cromwell quickly set up a High Court of Justice at the beginning of July 1654, with the aim of putting the conspirators up for trial:

«The Lord Protector has newly established a court of 32 judges [having brought forth] the prisoners that plotted against his person and his Council of State with the intention of putting Charles Stuart on the throne of these three kingdoms, and said to have assembled last Friday, having sent for the three main [prisoners], and having had the tax attorney read the accusations they were charged with and the depositions of the various witnesses that claimed them»[5].

«Il nuovo tribunale di 32 giudici stabilito nuovamente dal signor Protettore [fatti venire innanzi a sé] i prigioni che conspirorno contra la sua persona et suo Consiglio di Stato con intentione di rimettere Carlo Staurdo nel trono reale di questi tre regni, dette venerdì passato principio ad assemblarsi, facendo venire alla sua presenza tre de’ principali, ai quali havendo fatto leggere dal procuratore fiscale le accuse che li venivono date et le depositioni de’ diversi testimonij che le affermavono».

The trial went forward using practices that might be defined inquisitorial, in order to secure confessions from the accused rather than to hear their reasons. The prisoners were denied the chance of a fair trial with defense lawyers:

«[…] although the prisoners claimed them to be false [the accusations] and asked for time and assistance of lawyers to prove them so, and that having been denied by his gentlemen judges, for the laws that do not permit criminals of this kind to have advocates, but to answer for themselves and decry their innocence, we will have to see what the resolve of the gentlemen judges will be, having assembled today again to come to a final sentence, which will serve as an example to proceed against many others accused of having had a hand in this plot»[6].

«[…] benché i prigioni allegassero et affermassero essere falze, [le accuse contro di loro, ndr] et che domandassero tempo et assistenza di avvocati per provarle tali, il che essendoli stato negato da’ signori giudici, per essere contro le leggi, che non permettono ai criminali simili a questi d’havereavvocati, ma sì bene di rispondere loro medesimi, et così defendersi a viva voce, si spetta hora di vedere quello che i signori giudici risolveranno di fare, essendosi questo giorno di nuovo assemblati per venirne ad una finale sentenza, la quale servirà d’essempio per procedere contro di molti altri che vengono accusati di havere tenuto mano in questa congiura».

As follows from these comments, it wasn’t long before the men were sentenced: «This new court of High Justice has in this day [17 July 1654] sentences three of the main conspirators against the person of his Lord Protector and his Council of State to be hanged [Questo nuovo tribunale d’Alta Giustizia ha questo giorno [17 luglio 1654] condennato ad essere impiccati tre de’ principali della congiura contra la persona del signor Protettore et suo Consiglio di Stato]»[7].

«[…] the following Monday [20th July 1654] the sentence against only two was carried out, to one of which, having been a gentleman of good standing, his Highness relieved of the shame of the gallows, and of his head; the other was hanged, and the third, for having frankly confessed all the plot, was spared by his Highness. This new court will have to assemble to continue the trial of several others that for this cause are held prisoners in this Tower»[8].

«[…] il lunedì appresso [20 luglio 1654] fu esseguito la sentenza contro di due solamente, ad uno de’ quali, per essere gentil’huomo di buona estrazione, sua altezza li fece la grazia della forca, ma non già della testa; l’altro fu impiccato, et il terzo, per havere francamente confessato tutta la conspiratione, l’altezza sua ne fece sospendere la sua sentenza. Doverà hora di nuovo questo tribunale assemblarsi per proseguire il processo di diversi altri che per questa causa ritengono prigioni in questa Torre».

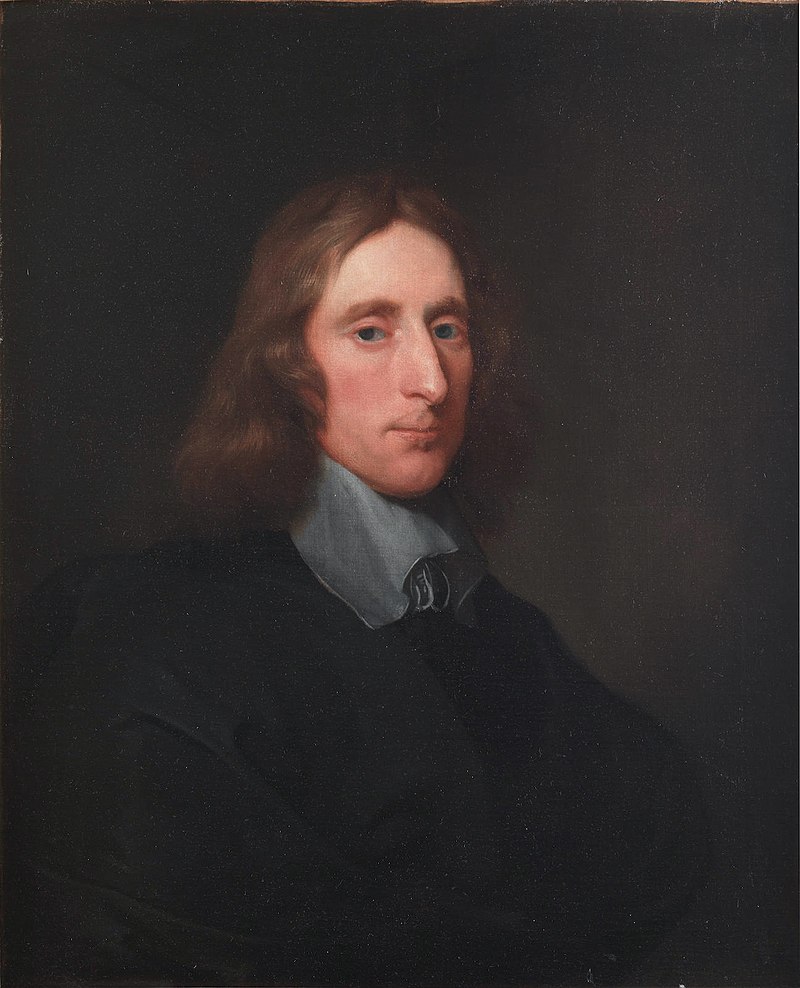

The arrests and sentencing continued throughout the summer of 1654. Cromwell’s power rested with the skilled police operations, thanks to which he resisted increasing pressures from Parliament and royalist factions. Upon his death in 1656, his son Richard couldn’t live up to his role as a successor, losing control of the Council of State and of Parliament – the latter restored the Stuart monarchy two years later, encountering almost no opposition.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Cromwell#/media/File:Richard_Cromwell_(1626-1712),_by_Gerard_Soest.jpg

Amerigo Salvetti’s story followed a similar path: he stayed at his post as the Granduke’s observer in London until his death in July 1657. His son Giovanni took his place[9], and, like Richard, was wholly inadequate and lost his post after the fall of Cromwell. The Grand Duchy kept correspondence with Bernardo Guasconi for London intelligence[10], a gentleman with a past in the English royalist troops, close to Charles II. Starting from 1670, Francesco Terriesi was the favored in his place[11], as a Florentine merchant residing in London.

Further readings:

Abbott Wilbour C., The Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell: Volume III: The Protectorate 1653-1655, Harvard University Press, 1945.

Drake George, The Ideology of Oliver Cromwell, in Church History, vol. 35, no. 3, 1966, pp. 259–72. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3162307.

Guizot François, History of Richard Cromwell and the Restoration of Charles II, Regno Unito, R. Bentley, 1856.

Hirst Derek, Concord and Discord in Richard Cromwell’s House of Commons, in The English Historical Review, vol. 103, no. 407, 1988, pp. 339–58. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/571185.

Little Patrick, Oliver Cromwell: New Perspectives, Macmillan Education UK, 2009.

Villani Stefano, Per la progettata edizione della corrispondenza dei rappresentanti toscani a Londra: Amerigo Salvetti e Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli durante il “Commonwealth” e il Protettorato (1649-1660), Firenze, Leo S. Olschki, in Archivio Storico Italiano, Vol. 162, No. 1 (599) (gennaio-marzo 2004), pp. 109-125.

Villani Steafano, Note su Francesco Terriesi (1635-1715). Mercante, diplomatico e funzionario mediceo tra Londra e Livorno, in Nuovi Studi Livornesi, 2002-2003, vol. 10, pp. 59-80.

Villani stefano, Guasconi Stefano, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 60 (2003).

[1] Archivio di Stato di Firenze (from now ASF), Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 49r, 5 giugno 1654.

[2] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 55r, 12 giugno 1654.

[3] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 49r, 5 giugno 1654.

[4] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 62v, 26 giugno 1654.

[5] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 74r, 17 luglio 1654.

[6] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 74r, 17 luglio 1654.

[7] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 75r, 17 luglio 1654.

[8] ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 78r, 24 luglio 1654.

[9] Villani Stefano, Per la progettata edizione della corrispondenza dei rappresentanti toscani a Londra: Amerigo Salvetti e Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli durante il “Commonwealth” e il Protettorato (1649-1660), Firenze, Leo S. Olschki, in Archivio Storico Italiano, Vol. 162, No. 1 (599) (gennaio-marzo 2004), pp. 109-125.

[10] Villani Stefano, Guasconi Stefano, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 60 (2003).

[11] Villani Stefano, Note su Francesco Terriesi (1635-1715). Mercante, diplomatico e funzionario mediceo tra Londra e Livorno, in Nuovi Studi Livornesi, 2002-2003, vol. 10, pp. 59-80.oy