[by Brendan Dooley]

Events after the recapture of the king at the end of 1647 precipitated rapidly. Amerigo Salvetti summed up the state of play since then in a long newsletter (we are now in December the following year).

He starts with the results of negotiations between king and Parliament, and the disagreement about the results of this, between the Parliament and the Army.

“The Isle of Wight conference for the settlement of differences between the King and Parliament came to an end, and the Parliamentary Commissioners returned apparently very satisfied, the King having condescended to the substance of all their propositions, but the soldiery did not approve of anything done in this conference, and is now in possession of the person of the king…” [ASFi, Med. Princ., 4202, cc. 760r-761v; London, 8/18 December 1648]

Conditions of the king’s confinement are miserable.

He “has been taken from the tower of Newport and brought by sea to a very severe prison called the Tower of Hurst, situated on the sea not far from the the Isle of Wight, a place of bad air and no amenities, where he has none of his servants with him, but only two or three soldiers, who keep him not as king, but as the greatest criminal in the world.”

Parliament appears to be overwhelmed by the presence of the army.

“Parliament does not dare to declare whether the king’s concessions are satisfactory and ought therefore to be accepted, especially now that a good part of the army, with the same general Farfax, has come (without asking Parliament for permission) to take quarters in this city, while the general occupies the king’s own palace.”

[…]

The army rules!

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:General_Thomas_Fairfax_(1612-1671)_by_Robert_Walker_and_studio.jpg#filelinks

“In short, the soldiery commands today, without any opposition: something that no one ever believed that this large and very populous city of London would so easily permit, and now it has even offered money and put together 160,000 scudi for the fear of being looted.

Thus we see that the things of this kingdom are in a very bad condition, everyone is very sure that they will end up killing the king, and with him also the monarchy, or at least the continuation of it down to those legally supposed to inherit it, in order to give it to someone of their choice; although it is likely that such an endeavor will encounter numerous obstacles and shed an infinite amount of blood, etc.”

Parliament attempts to assert itself one last time concerning concessions to the king, and the king’s confinement

“After twenty-four hours of consultation held day and night in the Chamber of the Commons, and after many disputations pro et contra, whether the concessions made by the King at the Isle of Wight Congress were to be declared satisfactory, it was finally concluded to find them sufficient and fundamental for a good peace. At the same time, unable to avoid taking notice of the king’s severe imprisonment, they declared that this had been done without their knowledge, and ordered some members to inform the general [Fairfax] about their opinion on these two points”

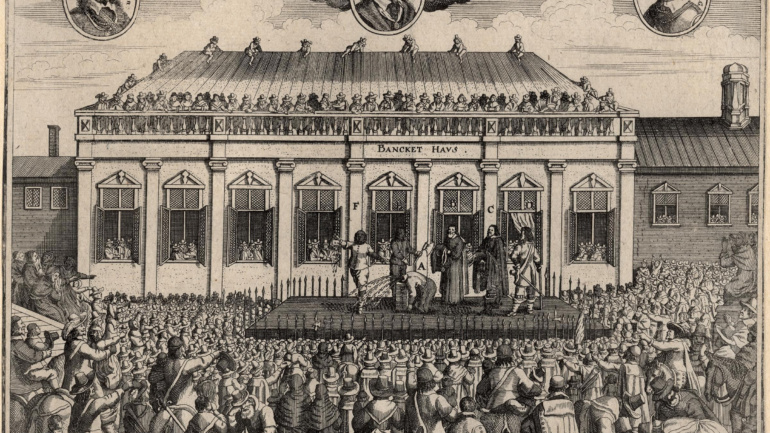

Fairfax reacts by ordering a removal from Parliament of all those members likely to object to the army’s intentions, and this is carried out by Colonel Pride (Pride’s Purge)

“…Without further ado, the following day [he] placed a heavy guard on the Chamber of the Commons, and imprisoned several members reputed to be great presbyterians and opposed to the designs and resolutions of the army. Hence it is clearly seen that not only are matters concerning the king in very bad condition, but the whole kingdom is heading towards its total ruin. The number of parliamentarians taken prisoner by the soldiery passes forty, and the same number are being prevented from entering Parliament, which now remains entirely composed as [the soldiery] wishes.”

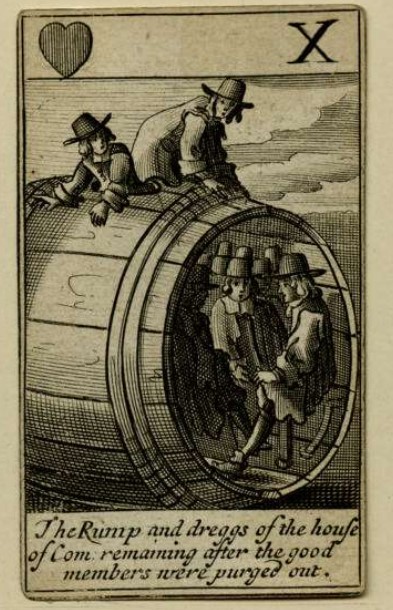

The resulting body, minus the excluded members, will be known as the “Rump Parliament,” in future years celebrated even in a deck of playing cards!

FURTHER READING

https://www.lookandlearn.com/history-images/M072516/Satire-on-the-Rump-Parliament

David Underdown, Pride’s Purge: Politics in the Puritan Revolution. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971

Pauline Gregg, King Charles I. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981

Carolyn Polizzotto, “Speaking Truth to Power: The Problem of Authority in the Whitehall Debates of 1648-9,” The English Historical Review, Vol. 131, No. 548 (2016), pp. 31-63