[Edited by Davide Limatola]

1654 in England represented a turning point in internal politics and, as a consequence, in diplomatic relationships with other continental European States. On the 16th December 1653, Oliver Cromwell dissolves the Republican Parliament and takes the title Lord Protector, a title that hides de facto dictator. For the first time in history, England is led by an outsider to the Royal Family. In Europe, many public comments circulate on the new path the English are going down, and the Granducato di Toscana is not an exception. Amerigo Salvetti is an informant to the secretariat of Ferninand II in London, he is an excellent source to explore some interesting aspects of British politics under the new Lord Protector. Through a precise and constant correspondence – in 1654 the avvisi penned by Salvetti are around 50, about 4 every month – the Florentine correspondent analyses three key aspects: domestic politics, diplomacy and military politics, especially on the Scottish and Irish fronts.

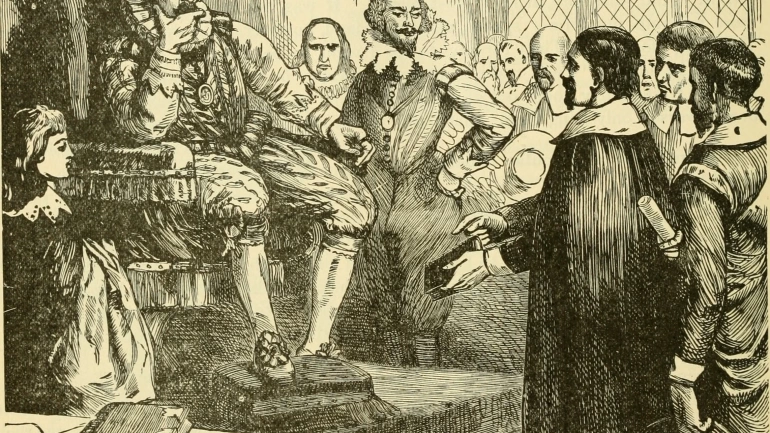

Since Cromwell’s power has already been consolidated in England, this set of documents written over the course of January 1654 explore novelties in domestic politics introduced by Cromwell. In particular, the new power dynamics between the new Lord Protector and the members of British Parliament are much discussed. In an avviso dated 9th January 1654, Salvetti stresses the fact that Cromwell aims to portray himself as a defender of old British values, rather than as a revolutionary, and hoe Cromwell chooses to uphold the Chamber of Commons in Parliament, but always under the watchful eye of the Lord Protector, to whom the veto on the Parliament’s decisions is reserved.

Salvetti writes:

«Fece dipoi il signor Protettore una sua assai ampla relatione, o sia dichiaratione, nella quale dichiarava, come voleva che si continuassero in Inghilterra i parlamenti accostumati di tenersi ogni tre anni, et come le provincie havessero la medesima libertà che solevono havere di eleggervi i loro deputati, benché con qualche restrintione et limite che le instrutioni che li haverebbe all’hora dato li prescriverebbero: che il prossimo Parlamento sarebbe convocato per li 5 di settembre 1654, et continuerebbe sin alli 5 di febraro avvenire, giustamente cinque mesi; et così di tre in tre anni si haverebbe Parlamento con le medesime condizioni, ma sempre con riserbare al signor Protettore il confermare o negare li atti che in esso si facessero»[1].

«The Lord Protector followed with an ample report, or rather a declaration, in which he declared that, as he wanted that the Members of Parliament continued according to their custom, to keep every three years, and how provinces had the same liberty as they used to to elect their representatives, but with some restrictions and limits from the instructions that would be prescribed: that the next session would be called on the 5th September 1654 and would continue until the following 5th February, rightly for five months; and so the sessions would be three in three years, and the Parliament would continue under the same conditions, but always with the discretion of the Lord Protector to approve or deny the acts they wrote».

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/cromwell-oliver-life/FQFT7dnfVqZhGw

Under the point of view of adherence to Anglican religious values, Cromwell continued on the beaten path, without introducing any relevant innovations. But, with much subtlety, Salvetti highlights the fact that the role models are Elisabeth I and che i modelli a cui rifarsi sono Elisabetta I e James I Stuart, to the detriment of Charles I Stuart, accused of having excessively Catholicising tendencies:

«Va medesimamente l’altezza sua formando la sua corte, dalla quale assolutamente n’esclude tutti i cattolici, contro de’ quali vuole che tutte le leggi fatte dalla regina Elisabetta et del re Jacopo continuino sempre nel loro vigore, et col medesimo siano esseguite»[2].

As mentioned the Lord Protector reserves every right to the last word on the decisions of Parliament, but every list of the names of the men who participate are analysed and purged of dislikeable names. Throughout August 1654, Cromwell received from every Province of the Kingdom the lists of names of the Lords to join Parliament.

Salvetti stresses how in these lists the are also (a few) counts and barons, now out of the Chamber of the Lords, abolished six months prior:

«Il signor Protettore col suo Consiglio di Stato va hora essaminando le persone che le provincie del regno hanno eletto per formare il nuovo Parlamento, osservandosi che fra di questi vi siano diversi colonnelli et uffiziali della armata, come alcuni ancora pochi conti et baroni, i quali col resto de’ titolati solevono per avanti formare da per loro una Camera col titolo della Camera superiore, et hora li converrà sentare et votare con la Camera delle Comunità»[3].

«The Lord Protector with his Council of State is now examining the people that the Provinces of the kingdom have elected to form the new Parliament, and noticing that among these these are sevel colonels and military official, and also some counts and barons, who used to with the rest of the titled [aristocracy] form their own Chamber with the title of Upper Chamber, and now they try to sir and vote with the Commons».

The formation of Parliament happens during September 1654. The documents written during this month, by Amerigo Salvetti to the secretariat of Ferdinand II, are the most interesting around the topic of dynamics between the Lord Protector and Parliament. In the documents, Parliament is described as it interrogates itself on how to make sure that the new Republican form of government adapts to the relics of the old monarchy. Members of Parliament are forced to bear oath with the following words:

«[…] io liberamente prometto et mi obligo di essere fedele al signor Protettore et alla Republica d’Inghilterra, Scozia et Irlanda, et in conformità del’Instrumento (in virtù del quale io sono stato eletto per servire in questo presente Parlamento) di non propuonere, né dare il mio voto d’alterare il governo stabilito in una sola persona et Parlamento»[4].

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/2wFzCDqaHoh14Q

The power of the Lord Protector seems to have no limit on the authority of the Chamber of Commons, and for this reason – Salvetti iterates this idea in several avvisi – Parliament seems to be particularly resolute on the issue of succession. Th matter of what is to happen to the title of Lord Protector upon the death of Cromwell, and the Commons seem intentioned to take on the paternity of the choice of the candidate. In an avviso of 6th November 1654, Salvetti notes:

«[…] alcuni [parlamentari, ndr] premendo che, conforme ad un Instrumento che questo signor Protettore fece stampare et publicare quando fu acclamato a quella sublime carica, tocchi perciò ai signori del Consiglio di Stato di fare detta elezione. Altri s’oppongono et insisteno che non altri che il medesimo Parlamento debba farla; et in caso di sedia vacante, alcuni pochi che da quelli saranno nominati, non già per farne direttamente l’elezione, ma solo con autorità di convocare un nuovo Parlamento dentro di pochi giorni, et quello fare detta elezione»[5].

«[…] some [Members of Parliament], stressing that, in line with an instrument that his Lord Protector has printed and published when he was acclaimed with such a title, it is for the Council of State to hold such an election. Some others opposed this and insisted that it is the same Parliament who should hold it; and in the case of a vacant sear, some few that will be nominated by others, not to have a direct election, but only with the authority to call a new Parliament in a few days’ time, having held the election».

These discussions will take up the whole final quarter of 1654 and will not die down for the following year. Salvetti continues to prove himself an excellent reporter on parliamentary dynamics and to inform Florence on the peculiarities of the newborn English Republica.

Further reading:

Abbott Wilbur C., The Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell: Volume III: The Protectorate 1653-1655, Harvard University Press, 1945.

Drake George, The Ideology of Oliver Cromwell, in Church History, vol. 35, no. 3, 1966, pp. 259–72. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3162307.

Gardiner Samuel R., History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate (3 vols.; London: Longs-man, Green, 1894-1901), III, 235.

Little Patrick, Oliver Cromwell: New Perspectives, Macmillan Education UK, 2009.

Loomie Albert J., Oliver Cromwell’s Policy toward the English Catholics: The Appraisal by Diplomats, 1654-1658, in The Catholic Historical Review, vol. 90, no. 1, 2004, pp. 29–44. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25026519.

Villani Stefano, Per la progettata edizione della corrispondenza dei rappresentanti toscani a Londra: Amerigo Salvetti e Giovanni Salvetti Antelminelli durante il “Commonwealth” e il Protettorato (1649-1660), Firenze, Leo S. Olschki, in Archivio Storico Italiano, Vol. 162, No. 1 (599) (gennaio-marzo 2004), pp. 109-125.

Worden Blair, The Rump Parliament 1648–53, Cambridge University Press, 1974.

[1]Archivio di Stato di Firenze (from now on called ASF), Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4203, c. 1045r, 9 January 1654.

[2]ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4203, c. 1068r, 13 February 1654.

[3]ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 95r, 14 agosto 1654.

[4]ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 128r, 2 ottobre 1654.

[5]ASF, Mediceo del Principato, Avvisi da Londra, vol. 4204, c. 153r, 6 novembre 1654.