[Edited by Antonello Mori]

The so-called First English Civil War saw its early stages with a lack of proper battles resulting in brief skirmishes and continuous mediation meetings between Parliament and King. The situation changed in October 1642, when in Warwichshire, in the West Midlands region, the armies clashed at a location known as Edge Hill[1]. The battle, whose outcome we now know to be inconclusive for both factions, marked the beginning of open hostilities between the two sides; King Charles I, his nephew Rupert of Palatine and other Royalist lords came face to face on the field against the Duke of Essex and Lord Feilding.

There is even a trace of this event in the avvisi written by Amerigo Salvetti, resident in London for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from which, however, the difficulty at the time of obtaining reliable information on the outcome of the battle is clear.

The first information about a possible clash comes with the notice of 30 October 1642, in which Salvetti reports the King’s displacement of troops .Letters dated 21 October arrived from the king’s camp, confirming that his majesty had 17600 infantrymen, 3000 horses and 2400 dragoons to fight against the Parliamentary army and then head towards this city:

«Arrivorno questo giorno lettere dal Campo del Re de 21 che confermano come Sua Maestà marcerebbe il giorno appresso con 17600 fanti, 3000 cavalli et 2400 Dragoni con resouzione di andare alla volta della Armata Parlamentaria et per venire a questa volta»[2].

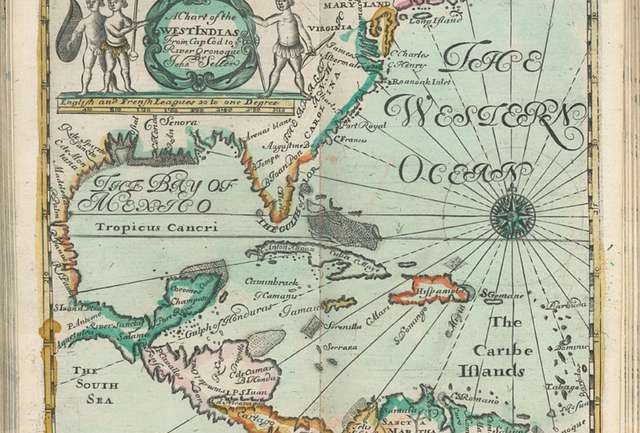

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:23_of_%27Edge_Hill-The_Battle_and_Battlefield;_together_with_some_notes_on_Banbury_and_thereabouts%27(11186001333).jpg

The next few weeks saw no news of any importance around the question, but with the avviso of 14 November 1642 the situation changes because Salvetti informs us that:

«The relationship of the battle between the Royal and Parliamentary armies is uncertain. The two factions provide news to glorify their side. The Royalists claim to have captured 36 insignia, 5 pieces of cannon, destroying 4 of them and killing 2000 parliamentary infantrymen. They also claimed to have driven away all the rest and looted the supplies. According to their claim, the King was present at the battle and once it was over he would declaim victory»

«La relazione della battaglia fra l’esercito Regio et il Parlamentario continua sempre assai incerta, ogn’uno raccontandola conforme al suo affetto. I Realisti raccontano come restorno padroni del campo di 36 insegne, di 5 pezzi di cannone, inchiodatone 4 ammazzatone più di 2 mila, messo in fuga il resto et preso quasi tutto il bagaglio, et come il Re si trovò presente a tutta la battaglia, il quale in una sua proclama fatta di poi, lui stesso pubblica d’havere havuto una gran vittoria»[3].

What the writer immediately highlights is how there is uncertainty surrounding the avviso, increased by the ‘propaganda’ built around it by detractors and promoters of either side. Salvetti, despite proving himself pro-monarchist, does not lack impartiality by reporting immediately that:

«The parliamentarians disregarding this proclamation claimed that the parliamentary army was the victorious one, saying that they had taken the Count of Linsi prisoner, who died two days later due to his wounds. Furthermore, they claim to have captured the royal banner and killed the knight Varve. Nevertheless, they declare that the standard was recovered by the Royalists. In the end, the parliamentarians admitted that some elements of their army fled shortly after the start of the battle».

«I Parlamentarij dall’altra parte non assentendo a detto proclama pubblicano la vittoria essere stata dalla lor banda, fondandola sopra del havere fatto prigione il conte di Linsi lor Generale, che due giorni doppo morì delle sue ferite, dalll’ havere preso il stendardo reale et ammazzato il Cavaliere Varve che lo portava benchè mezza hora appresso i realisti lo racquistassero, da che concludono essere seguo manifesto, che la vittoria restasse dalla lor parte. Confessano nondimento che 4 del lor reggimento d’infanteria con 15 cornette di cavalleria voltassero faccia, et se ne fuggissero dal bel principio della battaglia»[4].

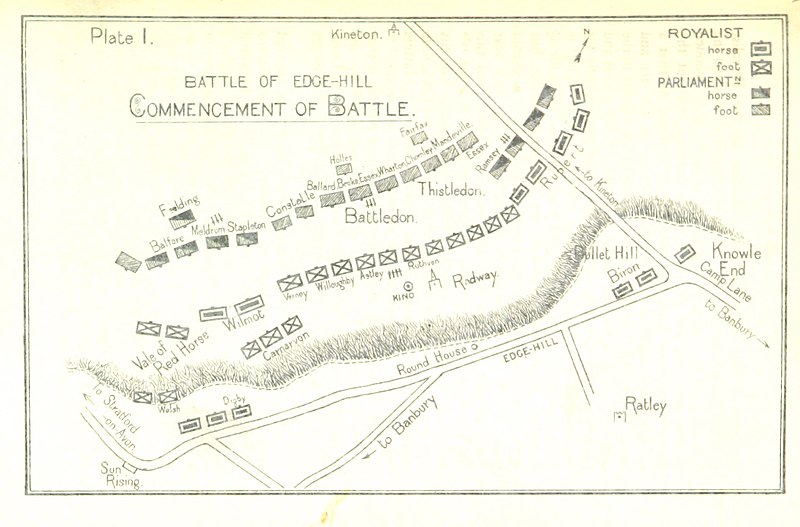

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prince_Rupert_at_Edgehill.jpg

It is therefore clear that both sides were trying to bring consensus to themselves, thus distorting information. What Salvetti does in this situation, however, is to immediately make it clear to the Grand Duke that it is not yet possible to come to any firm conclusions, but rather to wait. The man in fact affirms that:

«In conclusion, no firm conclusions can be drawn about this battle and discussing it is very dangerous».

«In conclusione questa è materia che qui non si può decidere, et il discuterne, è, fatta cosa pericolosa, perciò si va molto cauto nel parlarne»[5].

What seems certain is that the battle was not very bloody, but that some lords on the king’s side died:

«The battle was not bloody. It could have been much bloodier if the Prince Palatine had not gone on a looting spree too early. The Royalist army had lost the Count of Linsi, the Count of Montrose, Knight Varne and Baron d’Ambigni, brother of the Duke of Ricciemont. Baron Willibi and some officers were also taken prisoner. The parliamentary army lost the Baron of St. John and many others not remarkable».

«[…] non si può negare, che la battaglia non fusse molto sanguinosa, et che sarebbe stata molto peggio se il Principe Ruberto Palatino non havesse con la sua cavelleria seguitato i fuggenti, et datosi troppo presto alla preda del bagaglio. Dalla parte del Re vi sono restati morti il Conte di Linsi Generale, il Conte di Montrose scozzese, il Cavaliere Varne stendardo regio et il Barone d’Ambigni fratello del Duca di Riccemont et di prigioni il Barone Willibi con alcuni altri offiziali et dall’altra parte vi, è, restato morto il Barone di San Giovanni con altri d’inferiore qualità»[6].

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harvey,_Prince_of_Wales_and_Duke_of_York_Wellcome_M0016114.jpg

Today, we know that the battle was neither decisive nor bloody, and the whole thing was resolved, as can be seen from the documentation, with a kind of stand-off, in which neither faction had any particular benefit, but nevertheless attempted to gain prominence in the media. The documentation testifies, however, how difficult it was at the time to get reliable news around such a particular event, and how a foreign official reported such sensitive events.

Further readings:

Carlo Capra, Storia Moderna (1492-1848), Milano, Mondadori, 2011.

Christopher Hill, La formazione della potenza inglese. Dal 1530 a 1780, Torino, Einaudi, 1977.

Peter Young, Edgehill 1642, Moreton-in-Marsh, Windrush Press, 1995.

MAP, Miscellanea Medicea, 255, ins. 12, documento 53573, f. 13 verso.

MAP, Miscellanea Medicea, 255, ins. 12, documento 53575, f. 17 recto – f. 18 recto.

[1] About the whole event see Peter Young, Edgehill 1642, Moreton-in-Marsh, Windrush Press, 1995 and Christopher Hill, La formazione della potenza inglese. Dal 1530 a 1780, Torino, Einaudi, 1977.

[2] MAP, Miscellanea Medicea, 255, ins. 12, documento 53573, f. 13 verso.

[3] MAP, Miscellanea Medicea, 255, ins. 12, documento 53575, f. 17 recto.

[4] Ibid., f. 17 verso, 18 recto.

[5] Ibid., f. 18 recto.

[6] Ibid., 18 recto.